For many years, my trusty Sony Dream Machine Clock Radio ICF-C122 has served me well. In this post I will extoll its many virtues, and some of its vices too.

The first thing I love about my alarm clock is its appearance. It is basically a white cube with rounded corners and a glossy black face. The result is a sleek appearance, with controls concealed on the top and side, and a clean, readable face.

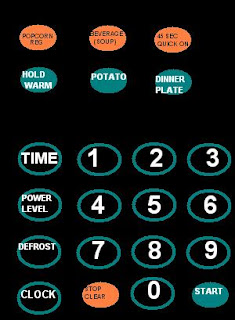

Now the controls. Pictured is the top of my clock radio:

At the top of the picture is a little slide. It is obvious just from looking that it is meant to be slid, and the little labels make it clear what the different positions do. These positions, from left to right, are Off, Radio, Radio Alarm, and Buzzer Alarm. When the slider is on one of the alarms, a red color underneath is exposed, giving a strong visual indicator that the alarm is set. What I like best, though, is that the only two positions I use, Off and Buzzer Alarm, are at the extremes, allowing me to slide the thing all the way, no fine-manipulation required. Furthermore, turning off the alarm when it goes off requires the slider to be moved, which is nice because it prevents a simple slap from turning it off.

The series of circular buttons below are Clock, H(ours), M(inutes), Alarm, and Sleep. These are for changing the clock and alarm time. The user simply holds down the button corresponding to what they wish to change (holding the alarm button changes the display to the alarm time), then presses the hour and minute buttons to increase the hour or minute until the desired time is shown. The great thing about these buttons is that they are all identifiable by feel. Clock and M are convex, while Alarm and H are concave; Clock and Alarm have little raised dots, H and M don't. The result is that every button has a unique feel. The purpose of this is to let the user change the time in the dark, or without looking at the top of the clock.

There are a couple annoyances here.

1. Holding down the hour or minute button increases the number pretty slowly, so I usually press them rapid-fire instead. I have gotten pretty good at this.

2. There is no way to decrease the hours or minutes, so changing the alarm from 9:00 AM to 8:00 AM requires many button presses. Not 23, though- only 9. This is because if you hold down the alarm or clock button and press both the hour and minutes buttons at the same time, the corresponding time is set to 12:00 AM. Without this feature, changing from 7:30 to 6:15 would require 68 button presses. With the feature, it requires 22. This cool feature makes this complaint pretty minor (though it took me many years to discover it).

Next to the four circular buttons is the Sleep button. I have no idea what it does. Hold it down, the screen shows 0:59. Press it, the radio comes on. I could guess what it's for, but I don't really know. In fairness, I never read the manual for this clock.

The large button at the bottom is the Snooze/Sleep Off. It does the typical snooze thing: hit it when the alarm goes off, and it will stop and go off 9 minutes later. I like this feature and use it a lot. This button also turns off the "sleep radio". I still don't know what this is all about.

The side of the clock has the radio controls: an AM/FM switch, a knob for volume, and a knob for frequency (which is displayed on the front). I rarely use the radio, but from what I can tell I have no complaints here. There is one potential problem, though. Any Seinfeld fan knows the many problems that can go wrong with an alarm, one of which is that if the volume knob is all the way off, the radio alarm will be silent. I don't use the radio alarm, but this is a potential flaw.

My final complaint is that the buzzer alarm is, like, the sound from hell. It certainly does its job well, but its not exactly a soothing way to get up. This is not really a design flaw- just a part of my personal relationship with my Dream Machine.

Though not totally a design thing, the last thing I love about my radio is that it still works after many years of smashing, knocking off tables, and other abuse. He's a great little machine, and he and I look forward to many more years of partnership.